Counting for Christmas … and beyond

The census that summoned Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem echoes centuries’ worth of data-gathering activity by parish churches – data that is now being put to new and surprising use in medical science.

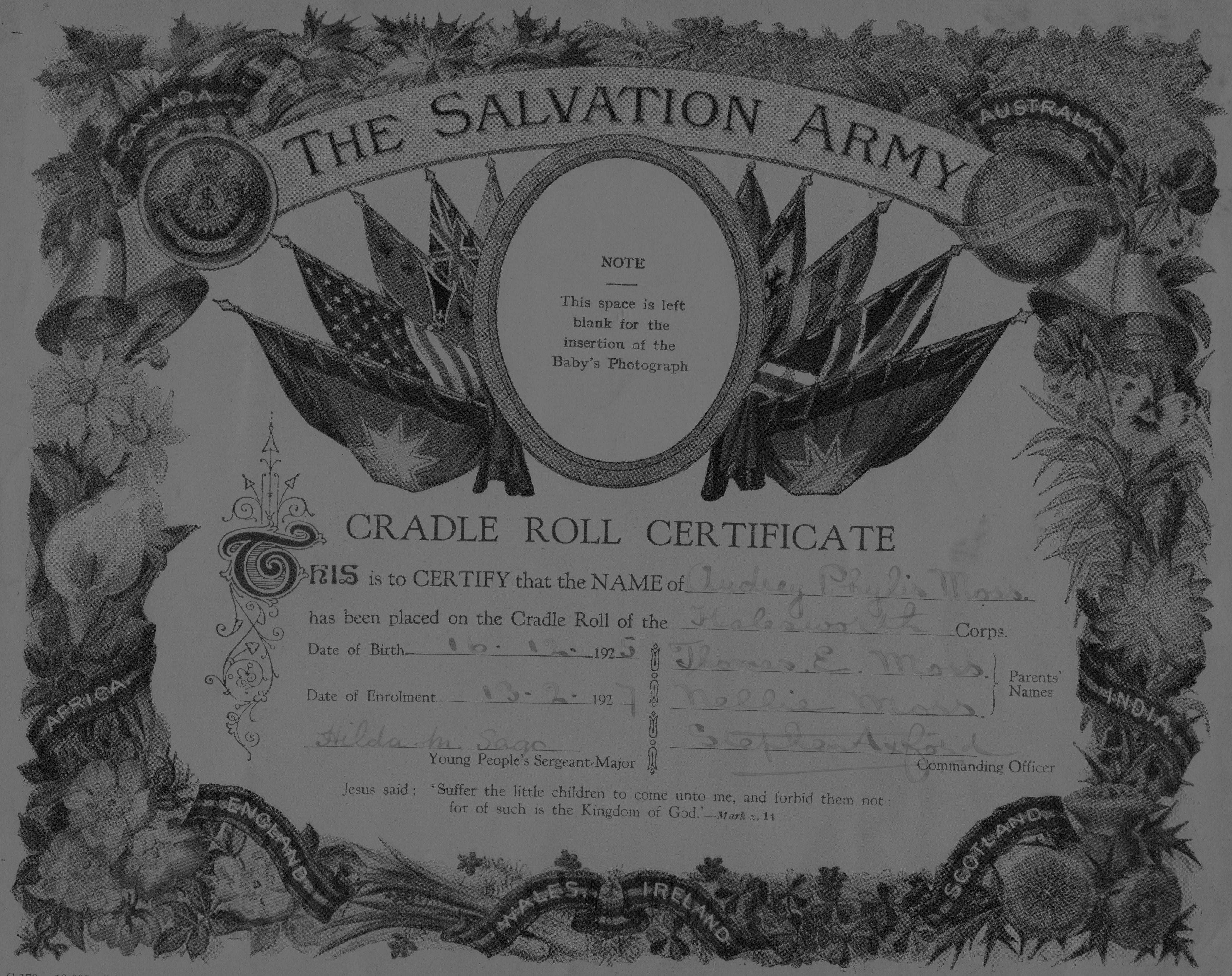

This Christmas, millions of people will journey to be with family. Many will reunite within their church communities at a carol service or Midnight Mass before sitting down together to celebrate over dinner. Without knowing it, they have passed through a data centre: many churches hold detailed and extensive records of the previous generations that have gathered there. These records, in dusty vestry books and elsewhere, are finding new relevance in the latest medical research.

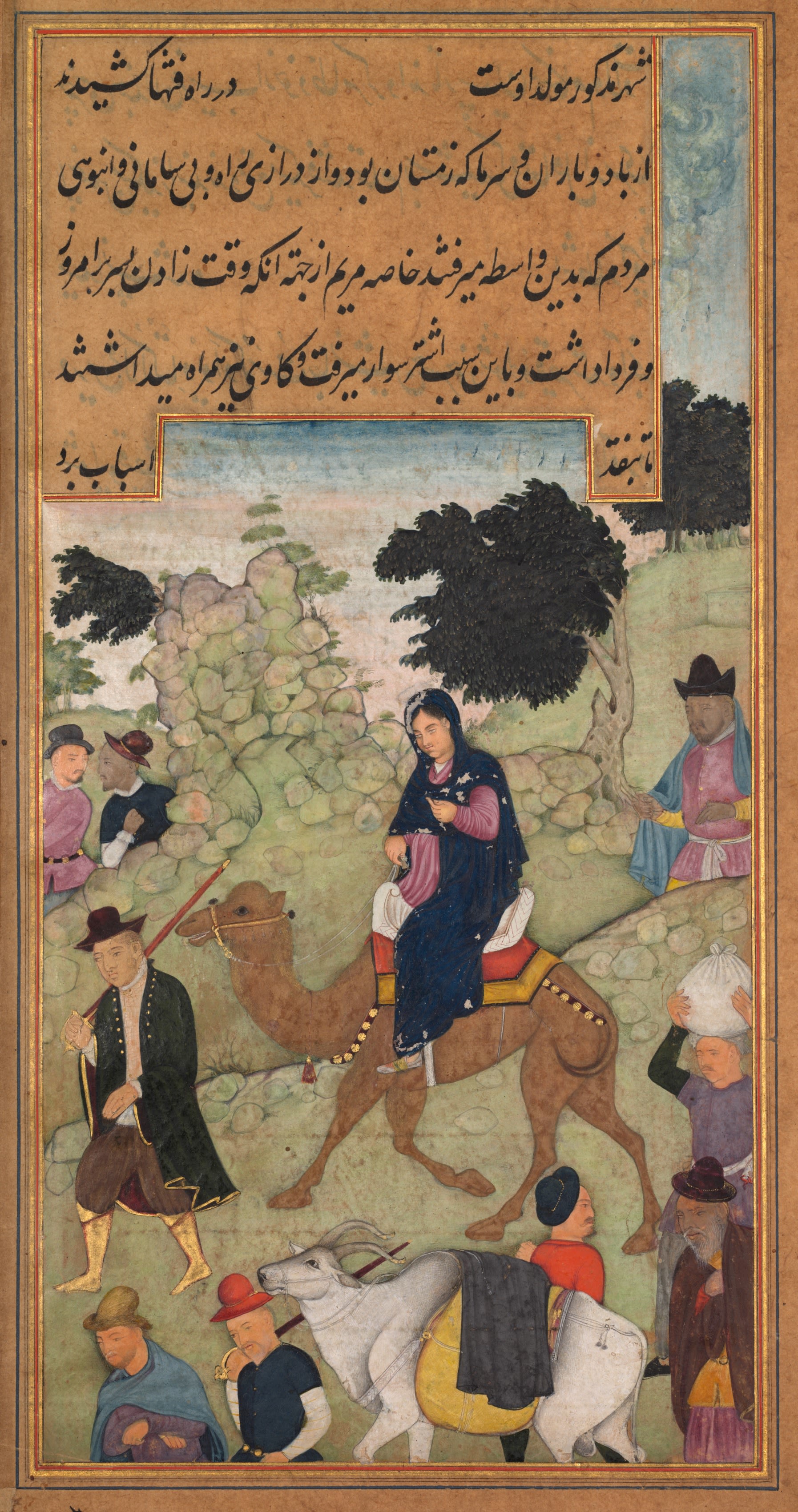

According to the Gospel of Luke, Mary and Joseph’s Advent journey was prompted by a census called by Caesar Augustus. The central role played by the census in this most fundamental of Biblical stories resonates strongly with the Church’s historical role in recording the lives of the communities it serves.

Although church records have long been used for personal genealogies, their use as demographic resources began around the 1950s. Records of births, deaths, and marriages opened up new avenues of research for scholars to study fertility rates, social mobility, and the changes of large groups over long time periods. Such data exists in Europe and beyond, throughout areas influenced by the global reach of Christian churches.

Most recently, this data has yielded new insights into historical disease, enabling researchers to study the human impact of past epidemics and pandemics.

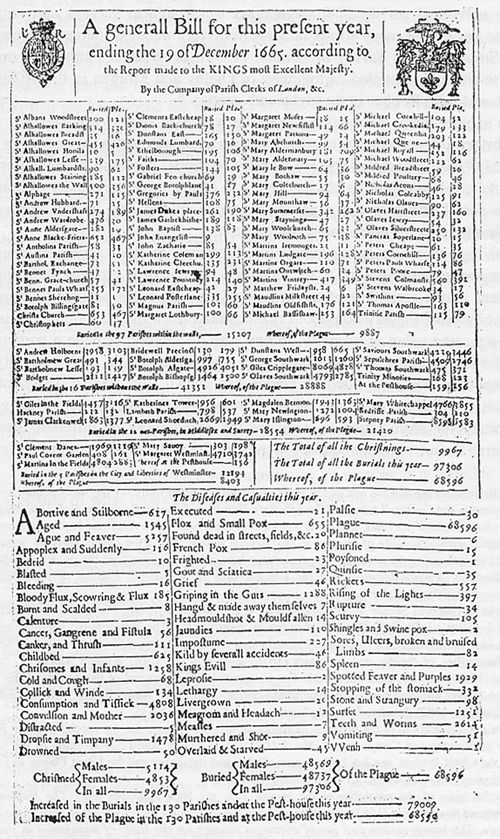

A tantalising parish record from London, in April 1665 records one Margarit [sic], daughter of a doctor, as perhaps the first plague death in the British epidemic of 1665-66. And compared across London, parish burial records reveal higher plague death rates for males than females, sparking further medical questions.

In 1611, the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks was charged with the task of publishing weekly mortality reports for London. In many cases, the data collected by parish clerks are the only surviving record for thousands of London's poor and destitute, offering a unique picture of life and death in the city.

Parish records also allow researchers to understand the impact of diseases such as smallpox, influenza and tuberculosis (TB) that were transmitted by European settlers to indigenous peoples, often devastating their populations.

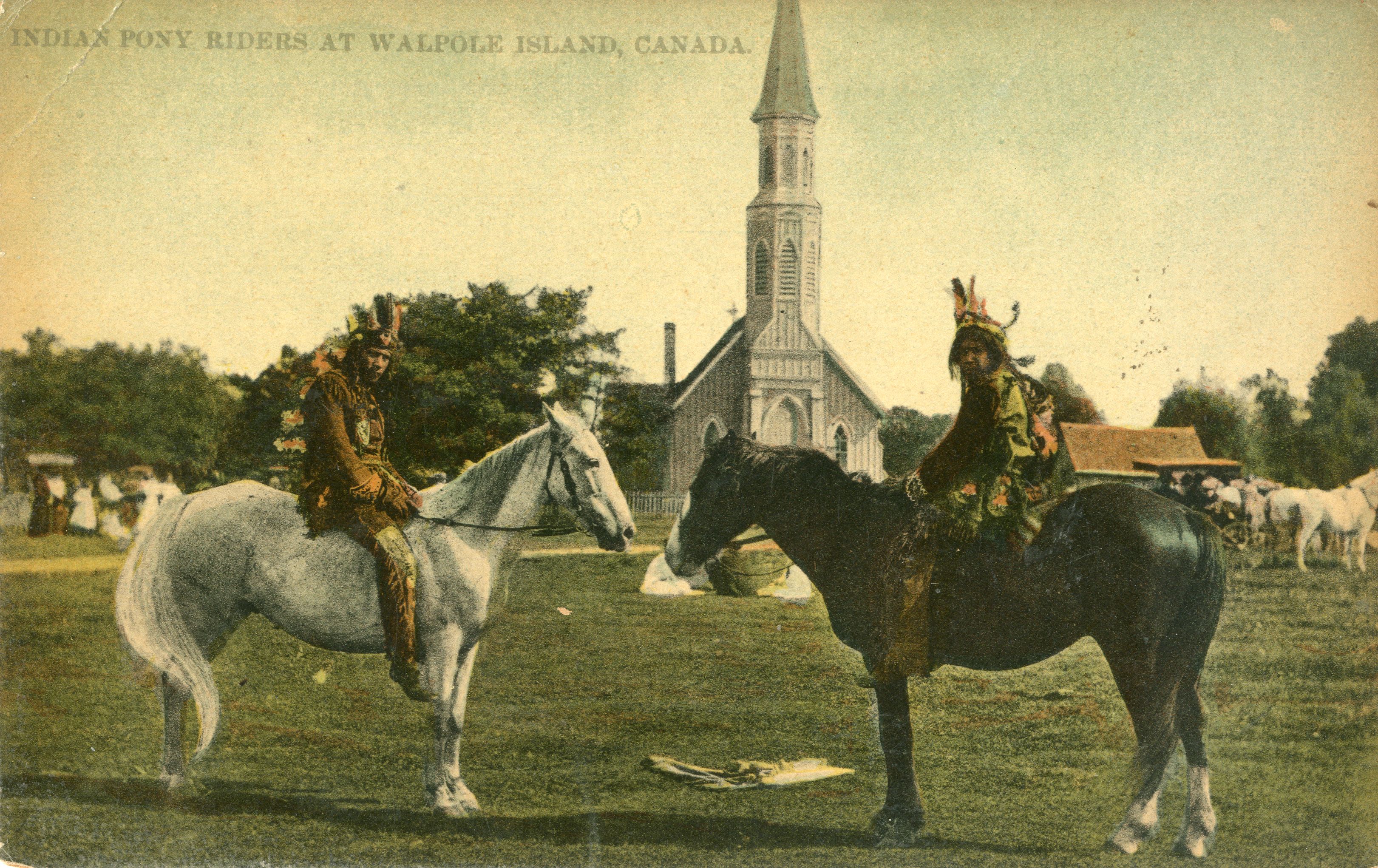

Take Walpole Island in Southern Ontario, the ancestral home of the Odawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwe peoples – who call the island Bkejwanong. Medical anthropologist Christianne Stephens has worked with Walpole Island Anglican parish registers to show that between 1850 and 1885, 61% of the deaths recorded were due to airborne diseases carried by the incoming settlers.

The parish data allows historical epidemiologists to track not only the cause of death, but also the age distribution of mortality. Records show that 82% of the deaths of young people were caused by TB infection.

This quantitative data is complemented by the more personal accounts also found in church records. The Methodist missionary Peter Jones, for example, recorded the ravages of TB amongst the peoples of Canada’s First Nations:

"The Indians die of inflammation of the lungs and consumption more frequently than any other disease… Many of them linger but a short time; others gradually waste away till they are reduced to skeletons, and at length, the little spark of life quits the enfeebled and emaciated frame."

The qualitative reports of church ministers and the quantitative data collected by parish clerks is currently revealing the long-term impact of European colonialism. Besides this, the data is being used to understand and improve the health of living aboriginal peoples across Canada. It demonstrates long-term trends, and the course of epidemic events. It reveals the social and economic factors that continue to shape community health profiles in the present: the on-going legacy of colonialism.

Such church records far predate the census-gathering efforts of governments. In the US, the first census was held in 1790 but only recorded the name of the head of the household. In the UK, the first census was 1801; in Latin America, Chile was the first state to hold a national census in 1853.

To go back beyond these dates, our family at the Christmas dinner table would have to turn to church records to discover its history. And as they pray for good health in the year ahead, they might be even more surprised to discover that the information collected centuries ago by humble parish clerks forms evidence for epidemiological policy today.

Discussion Questions

- Do you think that your family’s history is likely to be recorded anywhere? How does this make you feel?

- The data gathered by some churches reveals the damaging history of colonialism, yet is being used for positive purposes in the present. How can we best use historical data in other difficult areas, such as the Church of England’s connections with slavery? Or should we ignore it?

- What kinds of data, or experience, can churches gather in the present to help change society for the better? (Try not to get distracted by questions of GDPR!)

Further Reading

- The Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks

https://www.londonparishclerks.com/History/Company-History - UK Parish Registers before 1837

https://parishregister.co.uk/ - Mir'at al-quds available online at Cleveland Museum of Art.

A Stage Coach pulled by horses topped with large bags and turkeys for London. 1837. British library, public domain, by Thomas Kibble Hervey, R Seymour [illustrator]

A Stage Coach pulled by horses topped with large bags and turkeys for London. 1837. British library, public domain, by Thomas Kibble Hervey, R Seymour [illustrator]

Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem, from a Mir’at al-quds (Mirror of Holiness) of Father Jerome Xavier (Spanish, 1549–1617).

Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem, from a Mir’at al-quds (Mirror of Holiness) of Father Jerome Xavier (Spanish, 1549–1617).

Bill of Mortality compiled by the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks. © WikiCommons.

Bill of Mortality compiled by the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks. © WikiCommons.

Two indigenous men sit on horses in front of St. John the Baptist, Anglican Church, founded 1857. On Bkejwanong Territory (Walpole Island), pictured on a 1910 post card from the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive

Two indigenous men sit on horses in front of St. John the Baptist, Anglican Church, founded 1857. On Bkejwanong Territory (Walpole Island), pictured on a 1910 post card from the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive

Edwardian (1911) Christmas Card showing families gathering in Church at Christmas time.

Edwardian (1911) Christmas Card showing families gathering in Church at Christmas time.

To Download a free text version of this article to use with your congregation click below

We are looking for feedback on our stories, please help us by completing the short survey below.