Flat-out stupid

Flat-Earth beliefs are often linked with the ‘Dark Ages’ of Christian ignorance and dogma. But history shows lively medieval church activity in science - and a myth born of prejudice.

If you were to open an English-language high school history textbook from one hundred years ago, the story of the discovery of the Earth’s curvature would go something like this:

“Three hundred years before Christ, in the Library of Alexandria, the philosopher Eratosthenes used the measurement of shadows at different latitudes to accurately calculate the Earth’s shape, and even its size and distance to the sun. This scientific knowledge, widely known to the ancients, was lost when Christian mobs destroyed the Library and plunged the world into a Dark Age, ruled by the rigid dogma of the Church.

Over one thousand years later, Christopher Columbus bravely stood up to Catholic scholars by wagering that he could sail westwards to China from Spain, without falling off the edge of the world. Columbus succeeded in sailing to the Caribbean and back, breaking the authority of the Church and ushering in the secular, scientific innovation of the Renaissance.”

Nearly everything about this narrative is false.

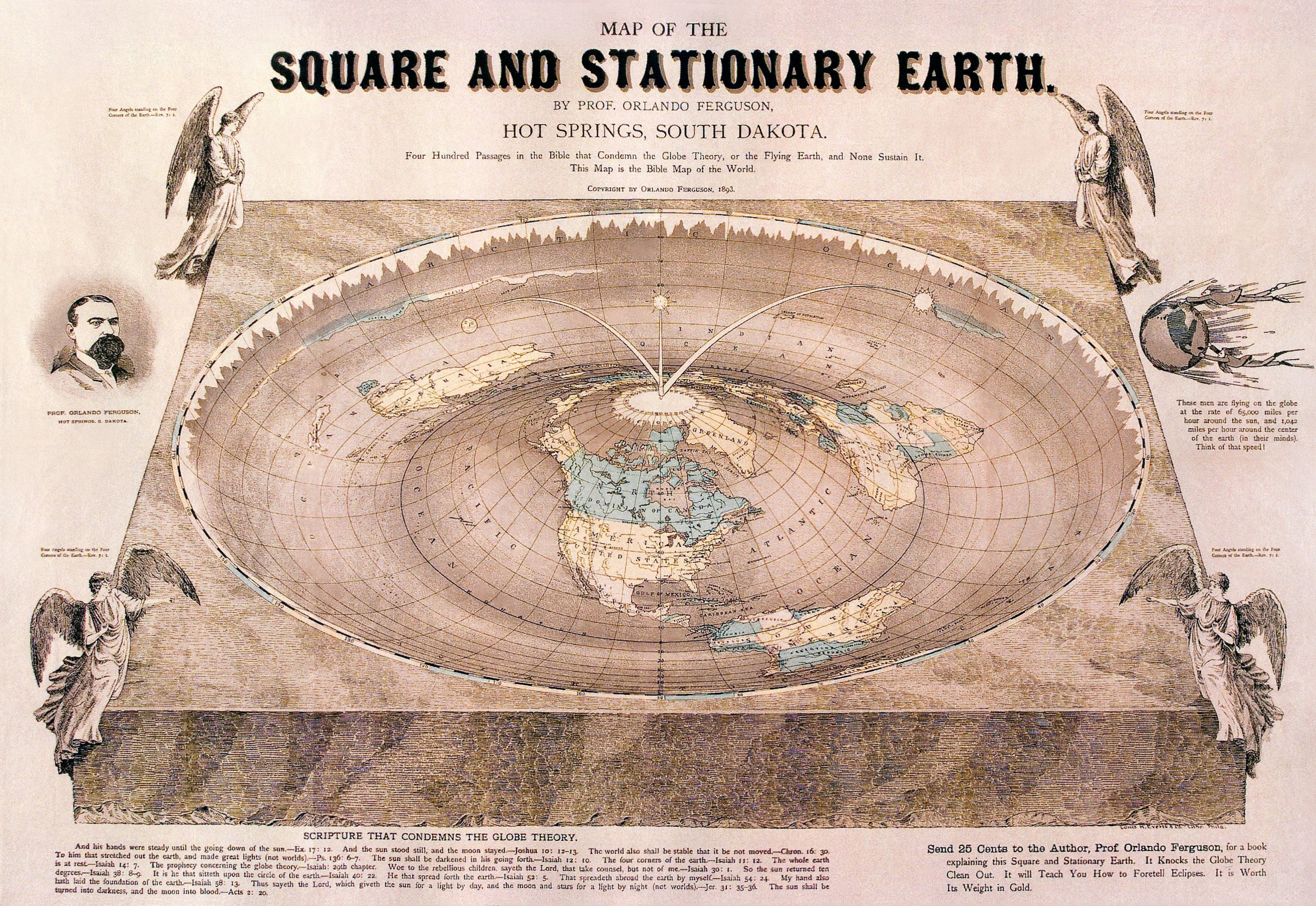

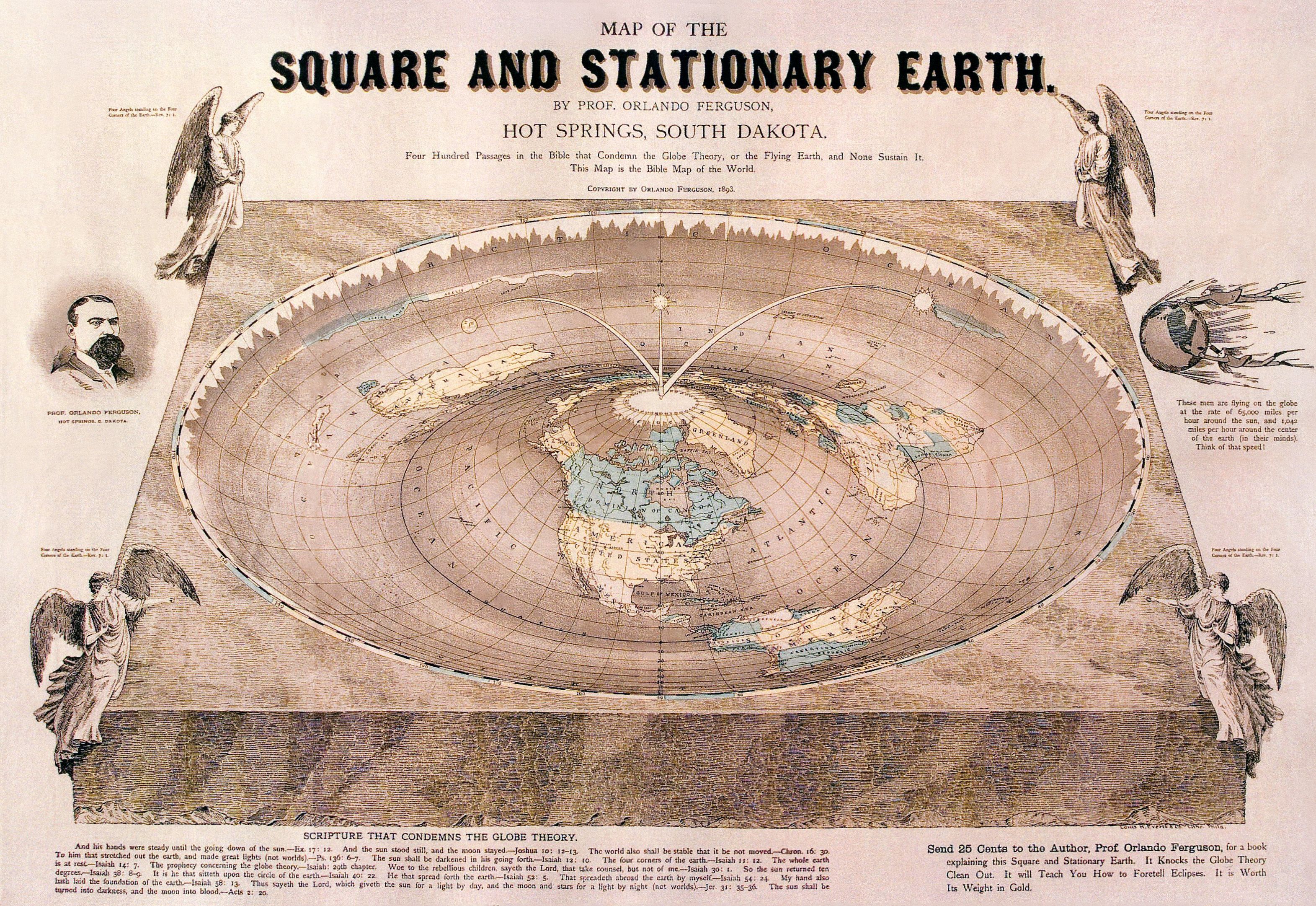

Map of the square and stationary earth (1893) by Orlando Ferguson of Hot Springs, South Dakota. Source: Library of Congress

Map of the square and stationary earth (1893) by Orlando Ferguson of Hot Springs, South Dakota. Source: Library of Congress

Flat-Earth beliefs are often linked with the ‘Dark Ages’ of Christian ignorance and dogma. But history shows lively medieval church activity in science - and a myth born of prejudice.

If you were to open an English-language high school history textbook from one hundred years ago, the story of the discovery of the Earth’s curvature would go something like this:

“Three hundred years before Christ, in the Library of Alexandria, the philosopher Eratosthenes used the measurement of shadows at different latitudes to accurately calculate the Earth’s shape, and even its size and distance to the sun. This scientific knowledge, widely known to the ancients, was lost when Christian mobs destroyed the Library and plunged the world into a Dark Age, ruled by the rigid dogma of the Church.

Over one thousand years later, Christopher Columbus bravely stood up to Catholic scholars by wagering that he could sail westwards to China from Spain, without falling off the edge of the world. Columbus succeeded in sailing to the Caribbean and back, breaking the authority of the Church and ushering in the secular, scientific innovation of the Renaissance.”

Nearly everything about this narrative is false.

Map of the square and stationary earth (1893) by Orlando Ferguson

Map of the square and stationary earth (1893) by Orlando Ferguson

Eratosthenes did successfully calculate the Earth’s size and shape by measuring shadows at different points in Egypt, and this knowledge was commonly accepted across the classical world. But this information was not lost because of the rise of Christianity.

As Christianity spread around the Mediterranean world, the Library had already gone into a terminal decline. Nor did the Church suppress classical knowledge; indeed, its monks played a vital role in preserving and reassembling it long before the Renaissance. Ancient Greek philosophy was central not only to medieval Christian metaphysics, but also to philosophy of the Islamic golden age.

It is true that a very few early Church figures explicitly rejected ‘pagan’ knowledge of the spherical Earth, due to their strict interpretation of scripture. The most prominent of these was the fourth-century theologian Lactantius. But while some writings of Lactantius were widely read by early Christians, his Flat Earth writings were not.

The sixth-century monk Cosmas Indicopleustes, another flat-earther, was even more obscure. He was mocked by the small number of eastern Christians who knew of him, and his Greek writing was never translated into Latin, the shared language of Christian scholarship.

Cosmas’ views on the Earth were only translated into English in the late nineteenth century. They appeared just in time to serve as ammunition for Andrew Dickson White, who exaggerated the monk’s importance as evidence for the thesis at the heart of his book A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom.

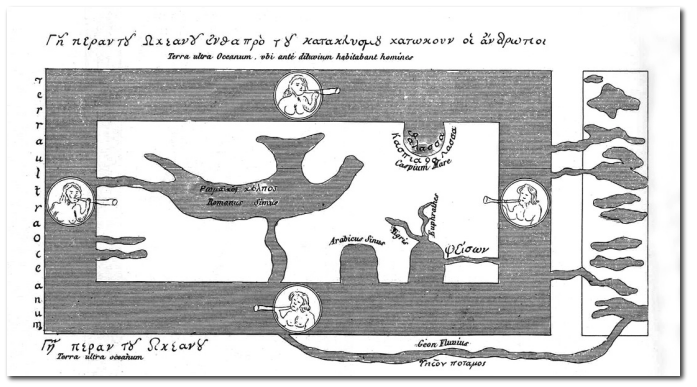

Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography, from later production. Source: Unknown

Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography, from later production. Source: Unknown

Eratosthenes did successfully calculate the Earth’s size and shape by measuring shadows at different points in Egypt, and this knowledge was commonly accepted across the classical world. But this information was not lost because of the rise of Christianity.

As Christianity spread around the Mediterranean world, the Library had already gone into a terminal decline. Nor did the Church suppress classical knowledge; indeed, its monks played a vital role in preserving and reassembling it long before the Renaissance. Ancient Greek philosophy was central not only to medieval Christian metaphysics, but also to philosophy of the Islamic golden age.

It is true that a very few early Church figures explicitly rejected ‘pagan’ knowledge of the spherical Earth, due to their strict interpretation of scripture. The most prominent of these was the fourth-century theologian Lactantius. But while some writings of Lactantius were widely read by early Christians, his Flat Earth writings were not.

The sixth-century monk Cosmas Indicopleustes, another flat-earther, was even more obscure. He was mocked by the small number of eastern Christians who knew of him, and his Greek writing was never translated into Latin, the shared language of Christian scholarship.

Cosmas’ views on the Earth were only translated into English in the late nineteenth century. They appeared just in time to serve as ammunition for Andrew Dickson White, who exaggerated the monk’s importance as evidence for the thesis at the heart of his book A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography.

All other medieval Christian authors either accepted the sphericity of the Earth, or did not find the topic important enough to argue over. Copernicus took it for granted that his audience did not believe in a flat earth, using this as a rhetorical way of promoting his sun-centred model of the cosmos. Thinking that the Earth was at the centre of the universe, he suggested, was as mistaken as Lactantius’ beliefs about its shape.

Indeed, next to the Bible, the most popular book of early-modern Europe was the late fourteenth-century Travels of Sir John Mandeville, whose author takes time to explain to the reader that the Earth is a globe. People in the southern hemisphere, he notes, are not upside down, and a traveller could theoretically head east and return home from the west. Amongst the readers of Mandeville’s travels was Columbus himself.

So where did the Flat Earth Error emerge from? This doubtful honour goes to Washington Irving, the American biographer and folktale-spinner of the early nineteenth century. In addition to creating classic stories like ‘Rip Van Winkle’ and ‘Sleepy Hollow’, Irving travelled to Spain in 1826. While there, he studied newly-open archives relating to the colonization of the Americas, using them to write a biography of Columbus. It was in Irving’s account where Columbus first appeared as a scientific pioneer against Catholic ignorance.

What drove Irving to depict Columbus—and the Church, and the Spanish officials—in this way?

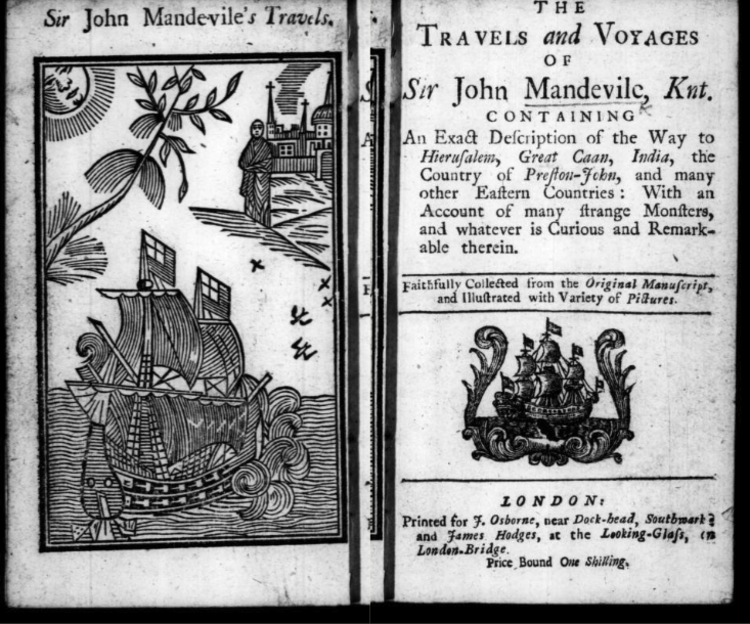

Frontispiece of 18th Century edition of Sir John Mandeville's Travels and Voyages (c.1357-1371)

Frontispiece of 18th Century edition of Sir John Mandeville's Travels and Voyages (c.1357-1371)

Frontispiece of Washington Irving's A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828).

Frontispiece of Washington Irving's A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828).

All other medieval Christian authors either accepted the sphericity of the Earth, or did not find the topic important enough to argue over. Copernicus took it for granted that his audience did not believe in a flat earth, using this as a rhetorical way of promoting his sun-centred model of the cosmos. Thinking that the Earth was at the centre of the universe, he suggested, was as mistaken as Lactantius’ beliefs about its shape.

Indeed, next to the Bible, the most popular book of early-modern Europe was the late fourteenth-century Travels of Sir John Mandeville, whose author takes time to explain to the reader that the Earth is a globe. People in the southern hemisphere, he notes, are not upside down, and a traveller could theoretically head east and return home from the west. Amongst the readers of Mandeville’s travels was Columbus himself.

So where did the Flat Earth Error emerge from? This doubtful honour goes to Washington Irving, the American biographer and folktale-spinner of the early nineteenth century. In addition to creating classic stories like ‘Rip Van Winkle’ and ‘Sleepy Hollow’, Irving travelled to Spain in 1826. While there, he studied newly-open archives relating to the colonization of the Americas, using them to write a biography of Columbus. It was in Irving’s account where Columbus first appeared as a scientific pioneer against Catholic ignorance.

What drove Irving to depict Columbus—and the Church, and the Spanish officials—in this way?

Sir John Mandeville's Travels and Voyages (c.1357-1371)

Sir John Mandeville's Travels and Voyages (c.1357-1371)

Frontispiece of Washington Irving's A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828).

Frontispiece of Washington Irving's A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828).

One reason had to do with the large-scale immigration of largely Catholic Germans and Irish to the United States during the 1820s. This set off a moral panic combining both anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment. Catholicism was widely seen as being opposed to free-thinking, innovative, democratic Protestantism. The prejudice combined with hardening racial sentiments caused by debates around slavery and a conflict with the former Spanish colony of Mexico. Having a Catholic from Southern Europe serve as the 'discoverer' of Protestant America was not appealing.

It is no coincidence that this was also the time when the idea that ancient Norse sailors ‘discovered’ the Americas, five centuries before Columbus, began to be popularized. The Danish scholar Carl Christian Rafn identified both colonial-era structures (Newport Tower in Rhode Island) and Native American artifacts (Dighton Rock in Massachusetts) as being of Norse origin. Unlike Columbus and his ilk, the Norse were safely Northern European, ancestors of Protestants.

Irving’s story enabled at least the Catholicism of Columbus to be ‘cured’. The devout Catholic of historical record was reinvented as a rebel against the Church, a pioneer of free thought and scientific experimentation. The story turned Columbus, in effect, into the predecessor of Luther and Copernicus. His voyage, and the founding of America, became the events which led to both the Scientific and Protestant Revolutions.

There is one final irony in Columbus being celebrated as a cutting-edge scientist. Columbus made a crucial mistake in his calculation of the Earth’s size because he ultimately relied on the ninth-century Arab scholar al-Farghani (incorporated in the work of a fifteenth-century French cardinal), without realising that Arabic miles are shorter than their Roman equivalent. This is why, upon reaching the Americas, he thought he was in the Far East.

Far from correcting Church officials over the true shape of the Earth, Columbus actually defended inaccurate ideas about the Earth’s size against Catholic geographers who, through their use of long-accepted science, were correct. Instead of being the discoverer of the true shape of Earth, Columbus had more in common with modern Flat Earthers who, against all consensus, characterise their beliefs on social media as the suppressed truth.

Engraving of Christopher Columbus by André Thevet (1502-1590). From Les vrais povrtraits et vies des hommes illvstres, 1584. Source: Harvard University Library

Engraving of Christopher Columbus by André Thevet (1502-1590). From Les vrais povrtraits et vies des hommes illvstres, 1584. Source: Harvard University Library

One reason had to do with the large-scale immigration of largely Catholic Germans and Irish to the United States during the 1820s. This set off a moral panic combining both anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment. Catholicism was widely seen as being opposed to free-thinking, innovative, democratic Protestantism. The prejudice combined with hardening racial sentiments caused by debates around slavery and a conflict with the former Spanish colony of Mexico. Having a Catholic from Southern Europe serve as the 'discoverer' of Protestant America was not appealing.

It is no coincidence that this was also the time when the idea that ancient Norse sailors ‘discovered’ the Americas, five centuries before Columbus, began to be popularized. The Danish scholar Carl Christian Rafn identified both colonial-era structures (Newport Tower in Rhode Island) and Native American artifacts (Dighton Rock in Massachusetts) as being of Norse origin. Unlike Columbus and his ilk, the Norse were safely Northern European, ancestors of Protestants.

Irving’s story enabled at least the Catholicism of Columbus to be ‘cured’. The devout Catholic of historical record was reinvented as a rebel against the Church, a pioneer of free thought and scientific experimentation. The story turned Columbus, in effect, into the predecessor of Luther and Copernicus. His voyage, and the founding of America, became the events which led to both the Scientific and Protestant Revolutions.

There is one final irony in Columbus being celebrated as a cutting-edge scientist. Columbus made a crucial mistake in his calculation of the Earth’s size because he ultimately relied on the ninth-century Arab scholar al-Farghani (incorporated in the work of a fifteenth-century French cardinal), without realising that Arabic miles are shorter than their Roman equivalent. This is why, upon reaching the Americas, he thought he was in the Far East.

Far from correcting Church officials over the true shape of the Earth, Columbus actually defended inaccurate ideas about the Earth’s size against Catholic geographers who, through their use of long-accepted science, were correct. Instead of being the discoverer of the true shape of Earth, Columbus had more in common with modern Flat Earthers who, against all consensus, characterise their beliefs on social media as the suppressed truth.

Engraving of Christopher Columbus by André Thevet (1502-1590).

Engraving of Christopher Columbus by André Thevet (1502-1590).

Questions for discussion

- Can you think of any other scientists who are celebrated as heroes? What qualities are attributed to them?

- Is it helpful to think of figures in science or faith as heroes?

- Is there a parallel between ‘Dark Ages’ insults and the charge that environmentalists ‘want to take us back to the Stone Age’?

Further reading

“Medieval Science with Seb Falk,” Undeceptions podcast, 25 July 2022.

Sharon A. Hill, “Flat-earthers as scientifical Americans: One message from ‘Behind the Curve’,” I Doubt It, 21 March 2019.

Brian Regal, “The Battle Over America’s Origin Story,” MonsterTalk podcast, 22 August 2022.

Edward Guimont, The Power of the Flat Earth Idea: History from the Marginalised (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2026).

Sebastian Major, "Columbus?", Part I, Part II, and Part III; Our Fake History podcast.

Jeffrey Burton Russell, Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians (New York: Praeger, 1991).

To Download a free text version of this article to use with your congregation click below

We are gathering feedback on this story please contribute to our survey.