Bones and Belief

How can science work respectfully

and collaboratively with worship?

The discovery of a casket of bones, hidden within the walls of an ancient church, offered a tantalising opportunity. Could scientists confirm that these were the remains of the saint for whom the church was named? Could they vindicate the faith of pilgrims, visiting for many centuries?

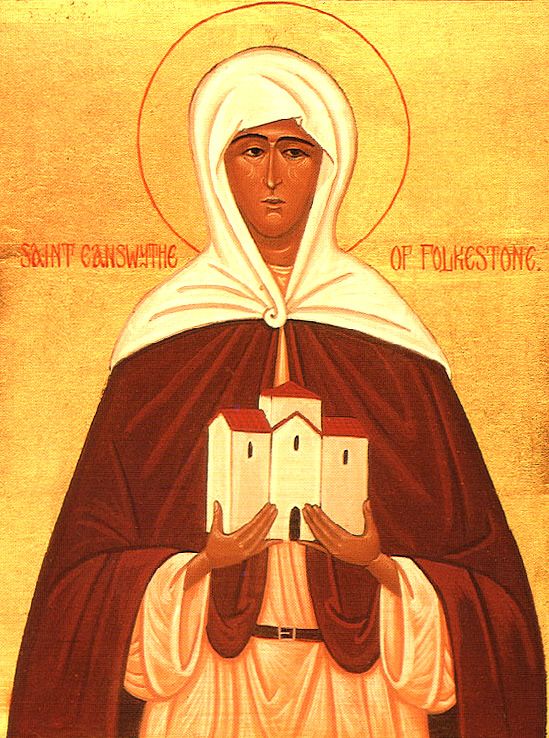

St Eanswythe is believed to be the first woman in England to have ruled over a religious community. She was only twenty years old, perhaps even in her teens, when her abbey in Kent was established around 650CE. Tragically, she died not long after.

St. Eanswythe, Abbess of Folkstone

St. Eanswythe, Abbess of Folkstone

A Photochrom image of the St Mary and St Eanswythe, Folkstone, taken in the 1890s. View from the north-east. | Library of Congress

A Photochrom image of the St Mary and St Eanswythe, Folkstone, taken in the 1890s. View from the north-east. | Library of Congress

In 2018, the congregation of St Mary and St Eanswythe made a difficult decision about whether to subject their relics to scientific analysis. Testing the bones might bring certainty to the faith of the community, but it also brought many risks. Would it be sacrilegious to subject the relics to scientific processes? And what if the remains were found to be those of a more recent woman, an older woman; or a man, or even an animal? Would the faith of the church be damaged?

As it turned out, science and faith worked together on the relics in respectful dialogue. Perhaps unexpectedly, they were able to do so by using methods worked out with Indigenous communities in the United States and elsewhere.

Until the late twentieth century, archaeologists often simply removed objects from the field and took them back to laboratories in Europe or North America for ‘proper’ analysis. Their actions echoed the way that colonialists helped themselves to materials and artefacts from conquered lands. Taking objects away from the field affirmed that European and American labs were the seat of knowledge and power.

Recent trends in archaeology, however, mandate a more collaborative approach, empowering local knowledge and ownership. Western scientists are getting used to working with local communities to ensure that research is done in mutually respectful and relevant ways.

In the case of St Eanswythe’s relics, English Christianity was the local tradition that needed to be involved in doing the science: the congregation, and the parochial church council were the local communities.

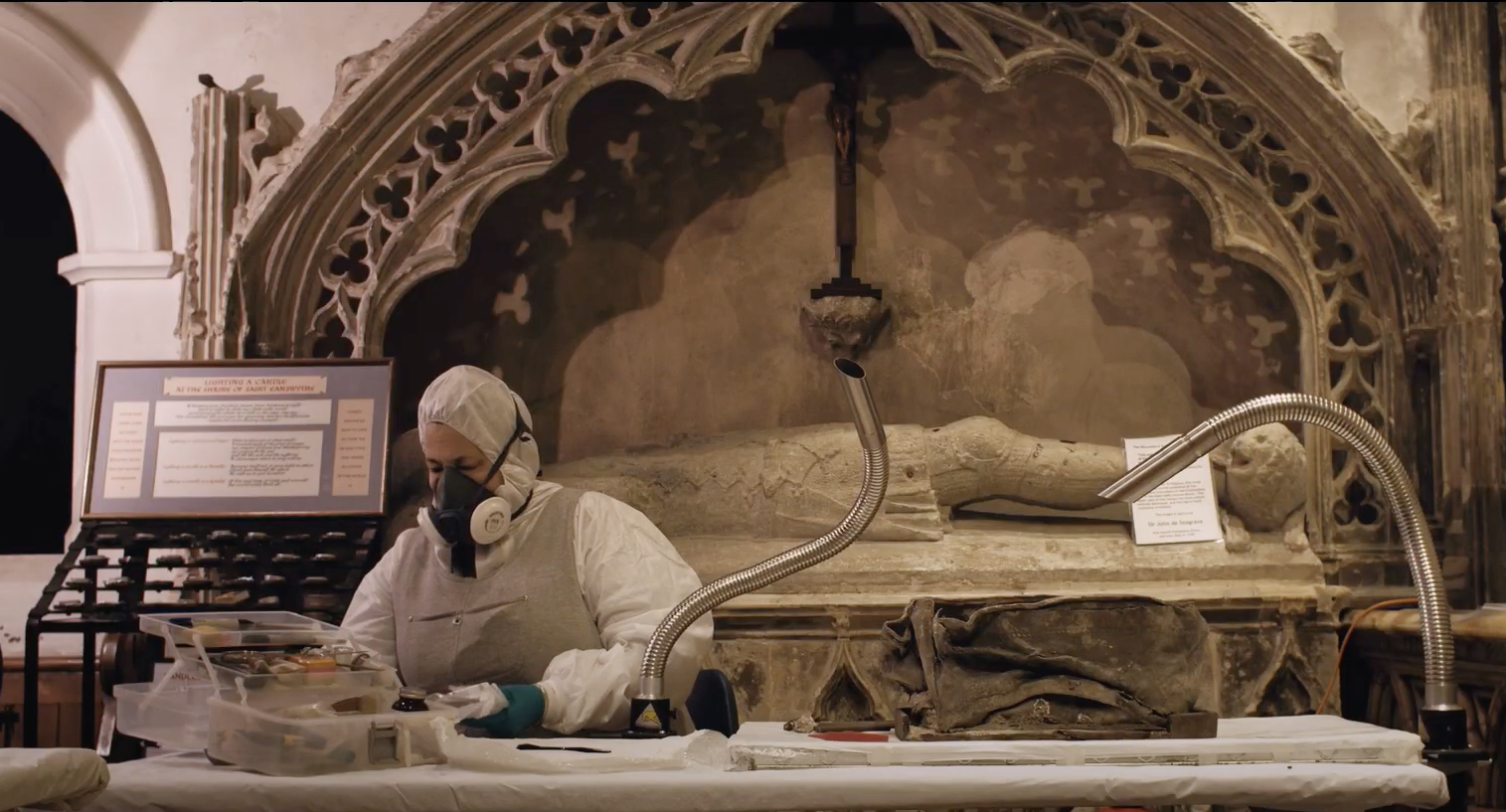

These communities decided that they did not want the relics removed to a laboratory. If the relics went to a lab, they would become mere bones. By staying in the church, they would remain sacred.

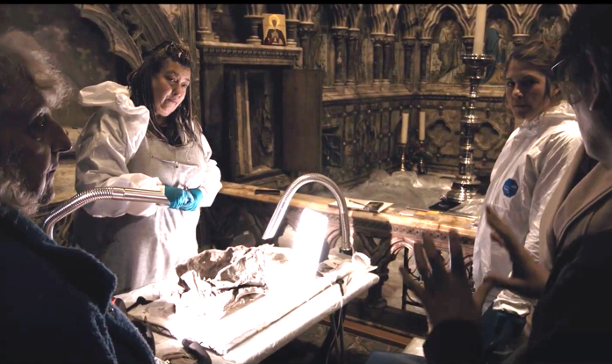

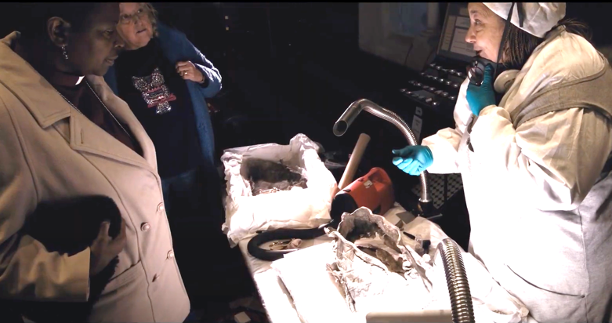

And so the scientists came to the church as guests, laying the bones out in the vestry for examination. The four walls that would normally see the priest robing before services now played host to investigators in hazmat suits and respirators, for fear of lead dust in the casket.

Church and science shared power and agency in this collaboration, working together to learn from the relics. The bones would keep their sacred meaning, as well as gaining fresh scientific interpretation.

The two parties not only worked, but also lived together. The whole team slept in the main body of the church, since the relics, in their vulnerable state, needed protection around the clock. Just for a few days, the scientists were drawn into centring the relics in their lives. For a brief time, they too saw relics as the centre of a living community, not mere bones for analysis.

These collaborative methods had a strong impact on the scientific members of the team. Even though the scientists defined themselves as ‘not religious’, one experienced a ‘strange and palpable sense of presence’ during the investigation. Another described a sense of Eanswythe’s ongoing ‘agency’, an ability to bring people together even long after her death.

One discovery that the scientists made very quickly was that the remains had disintegrated badly since the 1980s, when an earlier intervention had seen the relics put in plastic bags. The bags had made the bones damp, and caused them to decay more in the past 40 years than in the previous four or even fourteen centuries. It was a reminder that scientific methods are only ever provisional.

This sombre finding only increased the urgency for analysis so far as the whole team was concerned. They wanted to learn what information the bones could offer, before it was too late.

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

Still from Three Days in January | Filmed and Edited by Matt Rowe

And the results? The sex, the age, and the date of death turned out to be spot on for Eanswythe.

Yet something more than mere proof had been gained by both scientific and worshipping communities: a new way of doing science. Working together, the church and the archaeologists came to share the sense that science can, in seeking knowledge and making meaning, be another form of veneration.

Questions for discussion

- If you were in the congregation of St Mary and St Eanswythe, would you have voted in favour of the scientific analysis? Why/why not?

- The idea of saints’ relics can feel strange to some church cultures today. Are there other kinds of relics, though, that still bring communities together – whether for good or ill?

- Do you agree that science can be a ‘form of veneration’? Can you think of other examples?

To Download a free text version of this article to use with your congregation click below