Calculating Easter

How do you identify the unique resurrection moment in time?

Everyone knows the date of Christmas - it’s celebrated every year on December 25, isn’t it?

Unless, of course, you’re a member of the Orthodox Church, which celebrates on January 7 - but then again not if you belong to the Orthodox Church of Greece, which uses the earlier date.

While this difference in dates can have serious implications - as when the Orthodox Church of Ukraine decided to move its celebrations to December in order to divorce itself from Russian traditions - the distinction is actually quite simple. It depends on which calendar your Church uses to frame its liturgy: the Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar, or the Gregorian calendar, a more accurate method of counting developed in 1582CE.

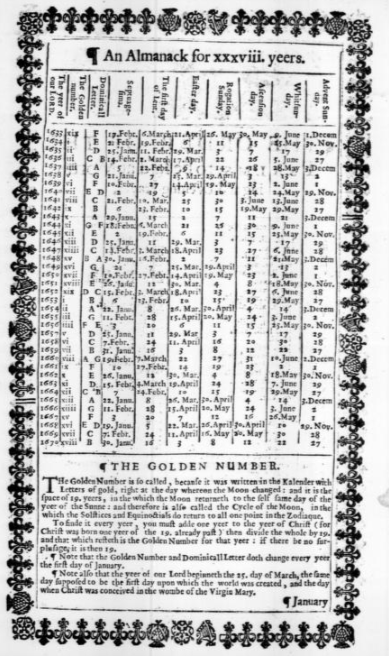

Book of Common Prayer, 1640. Credit: Internet Archive.

Book of Common Prayer, 1640. Credit: Internet Archive.

Figuring out when Easter should be celebrated is much more complicated than Christmas. In fact, it’s so complicated that calculating the date played a significant role in the history of mathematics and astronomy, as well as the development of universities in Europe.

At the heart of the problem lies the challenge of resolving a number of factors which derive from the (incompatible) solar and lunar calendars: the date of the spring equinox, the associated full moon, and initially, the date of the Jewish festival of Passover. Finally, of course, it has to fall on a Sunday.

Full moons recur on the same calendar date every eight or eleven years – a nineteen-year pattern known as the Metonic cycle. A (solar) calendar date will fall on the same day of the week every twenty-eight years. Together, they produce an Easter cycle of 532 years. Roughly twice a millennium Easter falls on the same day and date.

Things get worse when you realise the solar year – the time for earth to cycle the sun – is slightly more than 365 days. It’s closer to 365.2422 days, with leap years inserted into the Gregorian calendar to keep Earth dates adjusted to cycle times. Nor does the moon orbit the earth in exactly one calendar month. The same phase appears in the sky every 29.4306 days. It’s hard to synchronize human and heavenly clocks.

In essence, what was needed was a method of translating astronomical observation to the calendar in a way that would enable the date of Easter to be predetermined years in advance. The methods for doing this were known as computus and, to operate them, monks and clerics needed sophisticated astronomical and mathematical skills.

Mediaeval monastic schools taught their students the principles and debates underlying these calculations. Christians had to understand equinoxes, leap years, and planetary motions through the zodiac. They used astronomical tables, consulting ancient and contemporary observations of the sky. They brought together history, mathematics, and astronomy, using tables such as those developed in the third century CE by Hippolytus of Rome.

Bishop Hippolytus’ tables were based on eight-year cycles. By the fourth century these were replaced by an eighty-four-year cycle. In turn, this gave way to a nineteen-year cycle associated with the Alexandrian Church. In 525 CE, a Scythian monk named Dionysius Exiguus - the inventor of Anno Domini dating - adjusted that cycle to the Julian calendar.

Council of Nicaea 325. Fresco in Salone Sistino, Vatican. (Painted 1590). Credit: WikiCommons.

Council of Nicaea 325. Fresco in Salone Sistino, Vatican. (Painted 1590). Credit: WikiCommons.

Crucially, though, calculating and predicting the church year wasn’t just a technical or bureaucratic debate. It had immensely significant implications for international politics, for the history of science, and for the lived experience of faith.

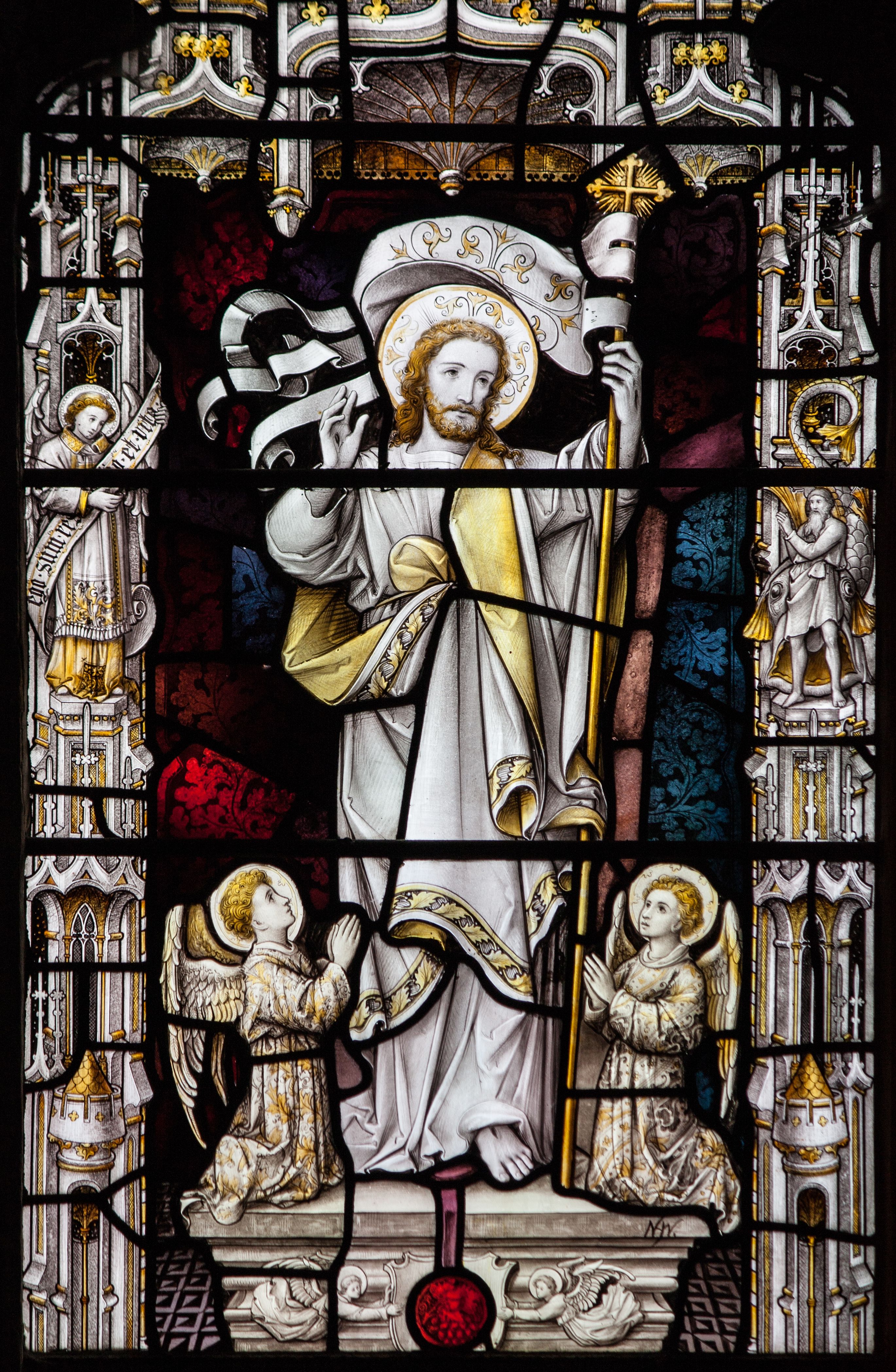

What was at stake here was identifying the precise moment in time at which the Resurrection had taken place - that singular, unique moment in which humanity had been redeemed, and when the entire Christian community must come together in thankful unity.

Unfortunately, the Christian community did not agree about when that moment should be. The first Council of Nicaea (325CE) had declared that all Christians should celebrate Easter together, but didn’t specify a method to calculate the date. While many churches followed Rome, some did not. Celtic Christians, on the Western edges of Europe, remained wedded to the eighty-four-year calendar.

Whitby Abbey (North Yorkshire). Credit: wwwuppertal/flickr

Whitby Abbey (North Yorkshire). Credit: wwwuppertal/flickr

This posed problems in places where the two traditions overlapped. In seventh-century England, King Oswiu of Northumbria found himself celebrating Easter while his wife, Queen Eanflaed, was still keeping her Lenten fast.

In 664, Oswiu called a synod at Whitby, hosted by the learned St Hilda, to decide the matter for his kingdom. After listening to both sides argue, he chose to follow Rome, marking the beginning of the decline of the influence of the Celtic Church in England.

Through many twists and turns, and over many centuries, the calculation of time – and of the church calendar - has been a story of science at work in the service of faith.

Questions for discussion

- What is the value of the church calendar in your life and/or in the life of your community?

- Would it be a good idea to unite the international church calendar? How would you feel about changing yours to fit in?

- Which forms of time measurement enhance your life, and which diminish it? How can you live better in time?

Further Reading

Aidan A. Mosshammer, (2008) The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era, (Oxford University Press).

How the Synod of Whitby settled the date of Easter. (English Heritage)

Frequently asked questions about the date of Easter (World Council of Churches)

To Download a free text version of this article to use with your congregation click below

We are looking for feedback on our stories, please help us by completing the short survey below.