The Nun and the Cheese

How Monastic tradition brought science to an ancient craft

You are about to read a story about connections - between food and spirituality, the universal in the elemental, and between God and cheese. This is the story of Mother Noella Marcellino.

Mother Noella is a Benedictine nun at the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Connecticut. She also has a doctorate in microbiology from the University of Connecticut. So how and why did a nun become a microbiologist and an artisan cheese maker?

Mother Noella Marcellino

Mother Noella Marcellino

A Benedictine monk inspecting Ermite cheese in the process of curing, Magog, Quebec, 1950 | Guy Blouin. National Film Board of Canada. Library and Archives Canada, e011175816

A Benedictine monk inspecting Ermite cheese in the process of curing, Magog, Quebec, 1950 | Guy Blouin. National Film Board of Canada. Library and Archives Canada, e011175816

Benedictine nuns follow the rule of St Benedict (480-547 CE) known as the father of western monasticism. Very little is known about St Benedict. We do know that he was sent to Rome from his hometown of Norcia, Italy to study. Not liking the political climate in Rome, he went instead to live in a cave for three years, and emerged to lay the foundations for a monastic community.

The motto of the Benedictine order is Ora et Labora – pray and work. Followers are encouraged to marry the practical with the theoretical. For Benedictines, working with one’s hands is to participate in creation. The precise nature of the work chosen by the monks and nuns of the order comes down to vocation. Benedictines encourage each other to pursue what they love, and to keep learning about their passions.

This is how Mother Noella came to cheese making. Through her love of cheese, her chosen spiritual path of looking closely at creation, and the encouragement of her order, she got an education in a field that could help her make better-tasting cheese – microbiology.

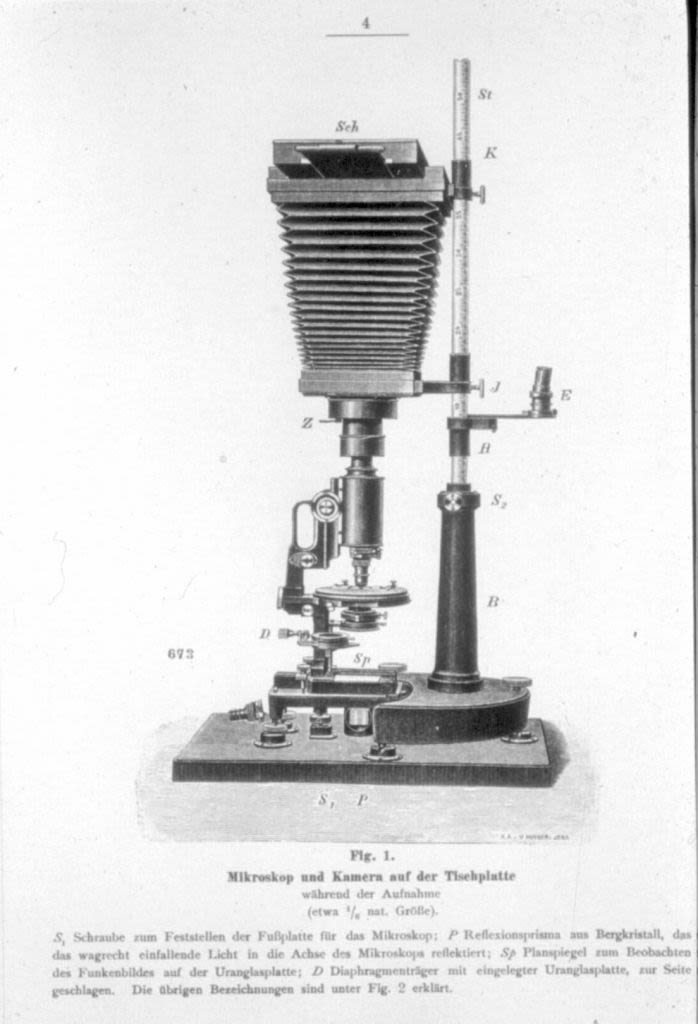

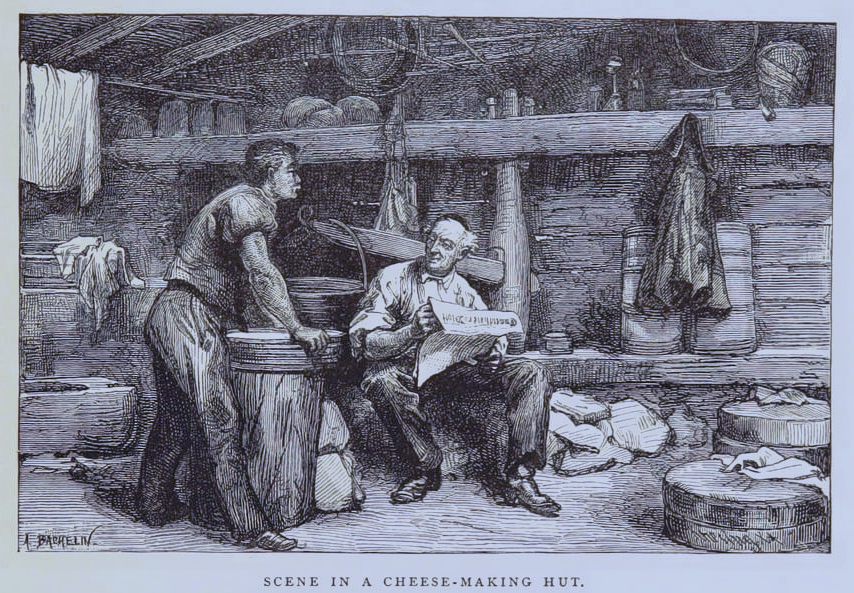

Cheese is made through liquid milk becoming solid and fermenting. To see if she could figure out precisely how it works, Mother Noella used light and electron microscopy to take snapshots of the fermentation process. She then earned a scholarship to study cheese in France, where she focused on Geotrichum candidum, a microorganism that contains enzymes to break down protein and fat and help cheese become – well – cheesier.

Through her studies, Mother Noella was able to genetically isolate a remarkable number of strains of the microorganism, mapping that diversity to types of cheese and regions in France. Her research confirms that traditional cheesemaking techniques have selected for a diversity of microorganisms that create the range of textures and the flavours we enjoy.

The work done by Mother Noella has had a profound impact on the practice of cheesemaking. Together with fellow microbiologists and cheesemakers, she managed to stop the FDA from banning the practice of ageing cheese in wooden barrels on the grounds that it was unsanitary.

So where is the sacred in Mother Noella’s practice as an artisan cheesemaker?

For Mother Noella, the milk from which the cheese is made is a gift from God. But cheese is special in that it is made through the interaction of enzymes with the milk. As Mother Noella explains “an enzyme moves in, brings two compounds together, and then moves away”. For Mother Noella, this makes the enzyme selfless. She reads selflessness into creation through microbiology.

But this is also about the relationship between the elemental and the universal, the part and the whole, themes deeply rooted in Benedictine spirituality. In the foundational biography of St Benedict, written by Pope St Gregory the Great (540-604 CE), we are told that St Benedict had a vision in which he saw the whole world in a ray of light. This theme of the divine illumination of the material world is formative for the Benedictine order. Benedictines are called to engage closely with creation, to get their hands dirty and see the universal in the particular. Mother Noella does this through science, by looking through a microscope to make better-tasting cheese.

Questions for discussion

- A cheesemaker doesn’t fit with the media image of a scientist as a physics boffin in a white coat. What other kinds of ordinary jobs in science, technology and medicine can you think of, perhaps within your faith community?

- What do you make of the Benedictine concept that to work with one’s hands is to participate in creation?

- If you were to follow Mother Noella’s example in learning more about your passion, what would you study?

Further Reading

To Download a free text version of this article to use with your congregation click below

We are looking for feedback on our stories, please help us by completing the short survey below.